Key Points:

- Ford engineers abandoned critical road tests with the Bronco II, because these safety tests were too dangerous for test drivers. In safety tests at speeds as slow as 30 miles per hour, the Bronco II repeatedly tipped up on its protective outriggers, clear proof that the vehicles were very likely to roll over in the hands of the driving public.

- Ford ignored its engineers’ recommendations to widen the track of the SUV and lower the center of gravity. In the spring of 1982, Ford engineers recommended that a 3 to 4 inch widening of the vehicle track, would produce a “major improvement” in “roll characteristics.”

- In anticipation of rollover litigation, Ford’s Office of General Counsel gathered more than 100 critical engineering documents before the production of the Bronco II and ordered engineers to “sanitize” them. Ultimately, many key documents disappeared prior to the production of the first Bronco II. These key documents were not disclosed to the National Highway Transportation Safety Administration (NHTSA) during the 1988-1990 Bronco II investigation. Ford said it “didn’t notice” that NHTSA asked for Bronco II development documents.

- When litigation began to heat up, Ford paid a former company engineer, David Bickerstaff, $5,000,000 over eight years to testify in a series of 30 rollover cases. In June 1990, Bickerstaff sent Ford a letter where he offered to be paid $4,000 a day to “assist you [Ford] in preparing me [Bickerstaff] in Ford’s favor”. After he sent the letter, but before he was paid by Ford, Bickerstaff testified (truthfully) that as a Ford engineer he was concerned about the Bronco II’s propensity to roll over, as indicated by its low stability index. After he was hired and paid by Ford, he testified that while working for Ford he was not concerned about the vehicle’s low stability index and that the stability index was nothing more than an “arbitrary number.” Bickerstaff also helped Ford rig a videotape designed to convince juries that the Bronco II was not likely to roll over, by loading a Bronco II with 900 lbs of lead shot on the floorboards and seats in a manner that artificially lowered the center of gravity. In April 2001, a federal judge concluded that, as a matter of law, Ford and its witness Bickerstaff engaged in a conspiracy to commit fraud. In June 2001, the South Carolina Court of Appeals decided that rollover victims could pursue a claim of “fraud upon the court” to re-open their case and seek a new trial because of Bickerstaff’s questionable arrangement with Ford.

Ford Knew The Bronco II Had Stability Problems

During the development of the Bronco II, it became clear that Ford would not meet the company’s stated safety and engineering design goals. The car was too high and too narrow to “reduce rollover propensity” or “respond safely to large steering inputs which are typical of accident avoidance or emergency maneuvers.”.

As early as February 1981, Ford engineers identified the Bronco II’s poor stability index as a key problem with the vehicle. According to engineering documents from that time, for an additional cost of $83 per vehicle, Ford could have made a substantially safer car. [Full document] | [Full document]. These changes were rejected by Ford management, however, because they would have delayed production and sale of the vehicle. Ford did not widen the SUV three to four inches until model year 2002, almost 20 years after the engineers’ warnings.

As part of vehicle development, test vehicles are driven on test tracks through several different types of turns and maneuvers. One such turn, a J-turn test, simulates a sharp turn to test the rollover propensity of the vehicle.

Internal Ford documents show that during a 1981 test drive the fully loaded Bronco II test vehicle tipped up on to its protective outrigger or had inside front wheel lift in every J-Turn run at a mere 30 MPH. Engineers, including David Bickerstaff, who was later paid by Ford to lie about SUV safety in 30 lawsuits brought against Ford by rollover victims, recommended that Ford consider widening the Bronco II to increase the stability index—that is, make it more stable and reduce the vehicle’s propensity to roll over.

Ford ignored the safety and design recommendations of its own engineers:

A March 17, 1982 “Bronco II Handling Evaluation” document showed that more than 9 turns resulted in lift off, and 5 turns resulted in outrigger contact, which means that the vehicle tipped on its side. With this document, Ford engineers presented Ford management with several options to decrease the likelihood of rollovers:

Development recommends pursuing items 1, 2, and 3 below if a small improvement in roll characteristics during a “J” turn maneuver is deemed acceptable, or pursuing item 4 below if a major improvement is required. Incorporation of item 4 would most likely cause a delay in Job #1.

1. Release a pitman arm that provides maximum toe steer and slows the steering system down. This action would affect turning diameter and require revised steering steps.

2. Release a higher ratio power steering gear.

3. Release a 1-1/8 inch diameter front stabilizer bar and delete all rear stabilizer bars.

4. Increase track width 3-4 inches.

— 3/17/82 Program Report. Page 2.

Ford chose Proposal 2 instead of the safer Proposal 4, which would have resulted in a “major improvement” of “roll characteristics,” because increasing the track width would delay “Job #1,” the scheduled date the first Bronco II would roll off the assembly line. In one test run configuration in early 1982, Ford engineers widened the prototype track two inches. This simple change prevented the vehicle from tipping over at speeds up to 60 MPH in the J-Turn, which was a drastic improvement from the original prototype.

Ford apparently did no other testing of a prototype with a widened track. In a subsequent Program Report in April 1982, Ford engineers repeated their recommendation that the Bronco II production vehicle needed to be widened 3-4 inches to reduce the possibility of vehicle rollover during sharp turns. This proposal was also rejected.

In addition to a delay in Job #1, management did not want to widen the track of the Bronco II because a wider vehicle would limit sales abroad. The narrow track of the vehicle would allow Ford to market the Bronco II in other countries, especially Japan.

Once it was clear that management would not permit the safer option of widening the vehicle 3-4 inches, Ford engineers, including Bickerstaff, evaluated other options to make the Bronco II less likely to roll. One Bickerstaff memo shows that engineers considered lowering the center of gravity of the vehicle by substituting 14-inch wheels for the programmed 15-inch wheels. Engineers also developed contingency plans to lower the tires, widen the track, and other changes in an attempt to decrease rollover propensity. Management finally agreed to widen the production level vehicle, but only 4/10 of an inch, not the recommended 3-4 inches.

1982 Bronco II Cancellation of Test Drives out of “concern about the safety of our track drivers”:

The engineers’ recommendations for a 3-4 inch widening of the track were not based only on design principles, but also on first-hand experiences on the test-drive track. Internal Ford documents and court records show that in 1982, Ford suspended driving tests of the Bronco II for fear that its own professional test drivers would be injured or worse in a rollover accident.

A Ford engineer explained under oath why the tests were cancelled:

Q. Tell the Jury, if you will, what happened in the last limits J-turn test that Ford did at the Arizona Proving Ground in May, 1982. What happened to that Bronco II?

A. The . . . under the J-turn maneuver, the vehicle went up on two wheels, the outrigger failed, it dug into the cement and pole-vaulted the vehicle over.

Q. And it landed on its top.

A. It rolled over. Where it landed, I don’t recall.

Q. So is it correct, sir, that the reason the Ford Motor Company stopped limit J-turn testing of the Bronco II vehicle in May, 1982, and went to the computer simulation was concern about occupant safety?

A. Well, its concern about the safety of our track drivers, yes.

Q. Yes.

A. And our engineers.

Q. So you stopped doing the severe limits J-turn testing in May 1982, because you were concerned about your own test drivers. Right?

A. Right?

Q. You were concerned about the safety of your own test drivers. Right?

A. Yes. Because of the . . . we couldn’t depend on the outriggers supporting the vehicle.

Q. Now, that was eight months before job one. Is that right?

A. That is correct.

— Deposition of Ford Engineer James McClure, pages 109, lines 4-21 and page 110, lines 1-10.

“Ford conducted no further pre-production on-road safety testing of the Bronco II.” After abandoning live limits tests on the track, Ford used the ADAMS computer model for final limits testing. Ford’s report of the ADAMS simulation demonstrated again that the Bronco II Production Level Vehicle experienced inside two-wheel lift at 32 MPH during a Lane Change Maneuver test, which is an emergency avoidance maneuver. Ford did not simulate the Lane Change Maneuver at high speeds despite the computer model’s capacity to do so.

Bronco II Dynamic Handling Simulation:

Document Excerpt: Bronco II Dynamic Handling Simulation:

Document Excerpt: Ammerman Trial:

Excerpt from document on EWG’s Report Suddenly Upside Down Vehicles: Ammerman Trial: The “J-turn” is a test “commonly used to evaluate the rollover performance of mother vehicles.” R. at 7009. The test is performed by keeping the steering wheel in a straight position then turning it and holding at that turn. R. at 7013-14.

Document Excerpt: Test Conclusions:

McClure J-turn Discussion:

Ammerman Trial – Bronco II:

Case Summary – Ford Motor Company v. Ammerman

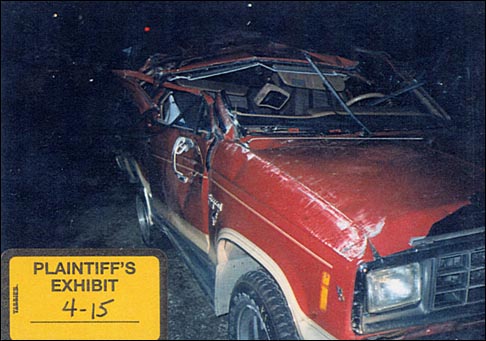

Lana and Pamela Ammerman (referred to collectively as “the Ammermans”) sustained severe and permanent injuries when a 1986 Bronco II 4×4 in which they were passengers rolled over. The vehicle was manufactured by Ford Motor Company. The Ammermans sued Ford on various theories of liability, and they also sought punitive damages. The case proceeded to trial by jury upon the theory of strict liability in tort pursuant to Indiana’s Product Liability Act. The jury returned a verdict in the Ammermans’ favor. Lana Ammerman was awarded compensatory damages in the amount of $400,000.00 and Pamela Ammerman was awarded compensatory damages in the amount of $4 million. The jury also awarded each of the Ammermans $29 million in punitive damages for a total punitive damages award of $58 million. On motion by Ford the trial court reduced the total punitive damages award to $13.8 million. Ford also filed a motion for relief from judgment which the trial court denied. Ford now appeals and the Ammermans cross appeal.

Ammerman Trial: Ford conducted no further pre-production on-road safety testing of the Bronco II

Disappearing Documents

Before a single vehicle rolled off the assembly line, Ford executives at the highest level knew that the Bronco II SUV was unsafe, and would roll over, injure and potentially kill a significant number of the people who bought it.

In a highly unusual move, prior to production of the Bronco II, the Ford Office of General Counsel (which reports to the CEO and Board of Directors) collected all the documents related to the testing of the Bronco II. On July 27, 1982, right after the Engineering Department signed off on the Bronco II, the Office of General Counsel began its document roundup .

Comprehensive identification of documentation of matters pertaining to Bronco II Handling has been requested by OGC. In order to establish what documentation is present in the files, please establish a list of documents which may have any bearing on Bronco II Handling, including a discussion of track width and vehicle height.

On August 3, 1982, at the request of the Office of General Counsel, Ford engineers began to collect all documents related to the testing and design of the Bronco II. Ford engineers testified that this round up was “unusual” and that all the documents went to the Office of General Counsel. Ford’s Office of General Counsel instructed the engineers to review each document related to the Bronco II and “sanitize” each document, including making additions or edits, if necessary, before turning the documents over to the legal department.

Engineers were ordered to “sanitize” documents:

After collecting, reviewing, and “sanitizing” the Bronco II documents, the Ford engineers turned the documents over to the Office of General Counsel. Even more troubling than this pre-production document round up is that fact that out of the 113 documents collected and stored by Ford’s Office of General Counsel, 53 documents mysteriously disappeared while in the custody of Ford’s attorneys. One of the missing documents was a “product change request form,” a standard Ford form whereby engineers request a modification to a proposed product. In this instance, the product change form apparently requested a two inch widening of the Bronco II track. Even though such a document would require many layers of sign off, it simply disappeared. Another document that disappeared was an attachment to a memo entitled “Seven Risk Factors”, which detailed risks associated with the design of the Bronco II.

In January 1983, a few months after this document round up, Ford manufactured and began to sell the first of 700,000 Bronco II SUVs. An additional 3.7 million Ford Explorers, with only modestly reduced rollover potential, were sold between 1990 and 2001.

Ford did not turn over these development documents, development testing results, or information about the cancellation of test drivers to the National Transportation and Safety Highway Administration (NTSHA) during the 1988-90 investigation of the safety of the Bronco II. The NTSHA requested the following from Ford:

Furnish the number and copies of all owner reports, … investigations, memoranda, and other records from all sources either received or authorized by Ford, or which Ford is otherwise aware, pertaining to (a) rollover, stability or similar performance or (b) the subject alleged defects of the Bronco II … (c) any information Ford may have comparing the Bronco II’s stability factor (center of gravity height) with other motor vehicles.

Identify the parties involved and describe any and all tests and analyses at (1) Ford, … or subject alleged defects, or (b) used to establish the stability of the Bronco II… Furnish copies of all reports, notes, tables, graphs, film, photographs, or similar documentation which were developed for each.

Furnish a copy of all documents not specifically requested which Ford believes are pertinent to the alleged defects and the resolution of the alleged defects, or were used in formulating its assessment of the alleged defects.

Ford said that it “didn’t notice ” that NTSHA asked for Bronco II development data.

The Story of David Bickerstaff

Just as Ford’s Office of General Counsel anticipated in the summer of 1982 when engineering documents were “sanitized” and collected, the Bronco II’s design flaws resulted in rollover fatalities and products liability litigation. The lawsuits began in the late 1980s.

As Ford attorneys reviewed their internal documents in anticipation of defending Ford in these rollover lawsuits, the name “David Bickerstaff” kept appearing. Bickerstaff joined Ford in the early 1970s as a light trucks engineer. He authored a series of engineering reports and memoranda that detailed Ford engineers’ concerns that the Bronco II’s low stability index — the ratio of the vehicle’s center-of-gravity height to its wheel track width — would result in rollover accidents. Ford attorneys suspected that Bickerstaff might be called as a witness for the victims of rollover accidents. Ford hired Bickerstaff and his consulting firm in 1989 to make sure that he was on the Ford payroll. (Many aspects of the Bickerstaff saga were reported by Jim Morris in the Dallas Morning News (4/20/02), but the documents underlying the federal court’s finding of conspiracy have not been public.)

In the spring of 1990, as Ford prepared its defense in a rollover case, Rosenbusch v. Ford, Ford lawyers decided to approach Bickerstaff and ask him to testify. Ford lawyers met with Bickerstaff in a Dearborn, Michigan, hotel room to discuss his relationship with Ford. Shortly after this meeting, Bickerstaff sent a letter to Ford’s outside lawyers. In this letter, Bickerstaff agreed to allow Ford to prepare him to testify “in Ford’s favor.” Bickerstaff set his fee at $4,000 a day. As determined by a federal judge in West Virginia, this letter marked the beginning of the conspiracy between Ford and Bickerstaff to lie in court, and to prevent victims of rollover cases from receiving compensation for their life-threatening, permanent injuries.

When Bickerstaff testified in the Rosenbusch case in the summer of 1990, however, Bickerstaff and Ford attorneys were still in negotiations over Bickerstaff’s fee. Bickerstaff had not yet been paid by Ford and he testified truthfully in the Rosenbusch case. Specifically, Bickerstaff testified that he was concerned about the Bronco II’s propensity to roll over as indicated by the low stability index, adding that, “the stability index is a major factor or a big factor in roll over propensity.”

Ford paid a former company engineer, David Bickerstaff, $5,000,000 over eight years to lie in a series of 30 rollover cases

This testimony is important because the Bronco II had one of the worst stability index ratings of any of the SUVs on the market. He also testified that the engineers who worked for him were concerned about the safety of the Bronco II. As the victim’s attorneys deposed Bickerstaff and asked him to review hundreds of engineering documents that detailed safety problems with the Bronco II, Ford attorneys quickly realized that if not managed properly, Bickerstaff could be a devastating witness against Ford.

Within 90 days of his July 9, 1990 deposition, Bickerstaff received his first check from Ford — a $100,000 payment for testifying in “Ford’s favor.” Bickerstaff received this $100,000 payment, despite the fact that he testified as a fact witness in the Rosenbusch case, not an expert witness. Fact witnesses are witnesses who testify to the factual events and circumstances of a case: who did what, when they did it, and where. Expert witnesses possess specialized or technical knowledge that will assist the jury or the judge in understanding the case, so experts testify to the why and how of the case. Fact witnesses are rarely, if ever, compensated for their time. Expert witnesses are typically paid for their time working on the case. They are not, however, paid to make specific statements in anyone’s “favor.”

In addition, Ford attorneys personally represented Bickerstaff at the deposition. This is rarely, if ever, done in the case of a witness who is not a plaintiff or a defendant in the case. This questionable arrangement suggests that Ford attorneys may have promised Bickerstaff that Ford would represent him personally to protect him against any repercussions from his testimony.

After Bickerstaff received his initial $100,000 payment, his testimony changed dramatically. The critical stability index was no longer a “major factor” in determining rollover propensity, but instead Bickerstaff stated, in direct contradiction to his testimony in Rosenbusch, that “the stability index . . . is strictly a comparative figure . . . an arbitrary number… [s]o I don’t attach any significance to it other than being, consistent maybe.” This lie is material because the Bronco II had one of the worst stability indexes of any SUV.

Bickerstaff also testified that the engineers working for him were not concerned about the Bronco II’s propensity to roll over. This lie clearly contradicted the Ford engineering documents he authored as well as his previous testimony.

Bickerstaff also inflated the level of his authority by claiming that he was the engineer who “signed off” and had the responsibility for deciding when the Bronco II was safe from a handling standpoint. But, Bickerstaff didn’t have that authority; he had left the company before the Bronco II was approved. This lie had the effect of unfairly bolstering his testimony as an expert, and according to the South Carolina Court of Appeals, was enough to allow the plaintiffs in the Chewning lawsuit to sue Bickerstaff and Ford for “fraud upon the court,” including the claim that Ford’s lawyers paid Bickerstaff to lie on the stand.

By 1996, Bickerstaff’s rates for testimony and depositions “in Ford’s favor” had increased from $4,000 to $10,000 a day. Bickerstaff also received many more $100,000 payments from Ford, totaling $5 million over the eight years. As Ford’s “star” witness, Bickerstaff was now able to earn more in a week than he made in a year when he was a Ford employee.

When asked about the nature of these payments, Bickerstaff lied again. He argued that the payments were not for testimony, but for his engineering consulting services. Yet, the 1996 letter regarding his no-bid, single source consulting “contract” defines his consulting services “for the purposes of Bronco II litigation, defense attorney briefings, my testimony given by way of deposition, plaintiff conducted depositions, trial testimony, exhibit preparation and document review.” The letter does not mention engineering work. With the help of David Bickerstaff’s testimony, Ford continued to settle Bronco II rollover cases around the country, including Brenda Goff’s case. In fact, Bickerstaff testified in deposition or trial testimony in at least thirty Bronco II cases across the country.

Ford lawyers met with Bickerstaff in a Dearborn, Michigan, hotel room to discuss his relationship with Ford.

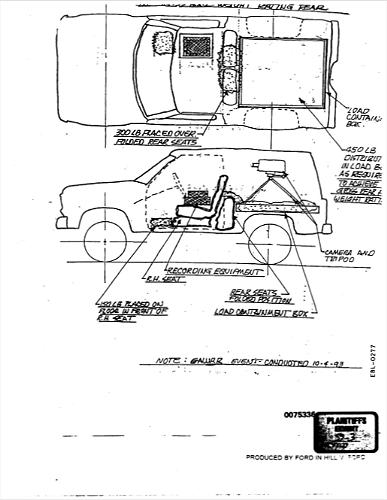

Bickerstaff also acted as a consultant for Ford to develop visual aids to present to juries during rollover trials. Bickerstaff, along with other Ford engineers, helped the Ford Office of General Counsel develop a videotaped test run of a Bronco II designed to convince jurors that the Bronco II did not have a tendency to roll over during avoidance maneuvers.

But instead of using crash test dummies or containers of water to simulate the normal weight distribution of passengers in the vehicle, Ford engineers, including Bickerstaff, followed what is apparently Ford’s standard practice for handling tests. Bickerstaff and the Ford engineers put nearly 900 pounds of lead shot on the floorboards and at the base of the seats, artificially lowering the center of gravity and countering the Bronco II’s natural tendency to roll over. The vehicle appeared deceptively stable in the videotape prepared for presentations to juries.

These facts were enough to convince a federal judge that — as a matter of law — Ford and Bickerstaff “engaged in a conspiracy to commit fraud” upon Brenda Goff, her family, and her dead son. The fraud specifically identified by the court in this case was Ford’s agreement to pay an expert witness to lie under oath. At least twelve other lawsuits are pending in courts across the country to determine whether settlements or past cases can be reopened because of Ford’s fraud on the court. Many of the other cases, including the Chewning case in South Carolina, deal with whether state law will allow a plaintiff to seek to reopen a closed case or a settlement because of an allegation of fraud. The Goff court, however, is the only court who has evaluated the evidence and answered the question whether Ford and Bickerstaff actually conspired to commit fraud.

When juries were presented with this evidence, they reacted harshly against Ford. In Commack v. Ford Motor Company, C.N. 93-33808, (Harris County, Tex. 1995), Bickerstaff was confronted on the stand with the 1990 “in Ford’s favor” letter. The jury awarded the victims $22.5 million in punitive damages. In Clay v. Ford Motor Company, C.N. 5:96CV2127 (N.D. Ohio 1998), Bickerstaff’s “consulting” arrangement with Ford and his ever-changing testimony were presented to the jury, who awarded the victims $17.5 million in compensatory damages.

During the Goff fraud trial in 2001, Bickerstaff was represented by criminal defense attorney Christopher Todd. After the 2001 West Virginia ruling in the Goff case, Bickerstaff fled to his native England.

Lawyers Taking Aim at Ford on Veracity of Expert

By Danny Hakim – New York Times

DETROIT, April 22 (2003)— Questions about the credibility of an expert witness in lawsuits involving rollover accidents are putting the Ford Motor Company on the defensive, as lawyers for accident victims press claims that Ford covered up evidence that its Bronco II sport utility vehicle was dangerous.

Last week, the South Carolina Supreme Court said that the estate of a man whose leg was crushed in a 1990 Bronco II rollover, Ray H. Chewning Jr., could seek to reopen a case he lost a decade ago. In its ruling saying there was a basis to reconsider the case, the court cited claims by Mr. Chewning’s lawyers that Ford paid the expert witness, David Bickerstaff, a former Ford engineer, to testify falsely on its behalf.

That decision followed a 2001 finding by a federal judge in a West Virginia case that there was evidence of a “conspiracy” between Ford and Mr. Bickerstaff to mislead the court. Ford settled that case, which involved a fatal accident, within two days of the judge’s finding.

Plaintiffs’ lawyers hoping to reopen scores of accident cases around the country claim that Mr. Bickerstaff, who helped develop the Bronco II in the early 1980’s, was paid millions of dollars after leaving Ford to alter his testimony about the vehicle’s performance on early safety tests.

Before he became a paid witness for Ford, he said in a 1990 deposition that he had concerns about the Bronco II’s stability. But after receiving the payments, he dismissed plaintiffs’ lawyers’ assertions in other cases that the vehicle — the predecessor to the Ford Explorer — had not performed well on the safety tests.

Ford officials have adamantly denied the claims of misconduct, and the company has succeeded in preventing some cases from being reopened. No court has ever concluded that Ford or Mr. Bickerstaff engaged in fraud.

“There is no basis for allegations that David Bickerstaff changed his testimony as an expert witness for Ford,” said Jon Harmon, a Ford spokesman. Ford, he added, “conducts its participation in legal proceedings with absolute integrity.”

Deaths & Lawsuits

It was estimated that 260 people had died in Bronco II rollover crashes, a rate that is several times more than in any similar vehicle according to the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety. By 1995, Ford had paid $113 million to settle 334 injury and wrongful death lawsuits. A class-action settlement with owners of its controversial Bronco II provided “new safety warnings and up to $200 for repairs and modifications.” Ford ended production of the Bronco II in 1990, but “always contended that rollovers are overwhelmingly caused by bad driving or unsafe modifications to the vehicle.”

Individual lawsuit examples include famed jockey Bill Shoemaker, that awarded him one million dollars. Shoemaker was paralyzed from the neck down after rolling his Bronco II in California in 1991 while intoxicated. Thereafter, he was confined to a wheelchair. The largest award involving the Bronco II up to 1995 was a $62.4 million verdict for two passengers, one of whom who received brain injuries and left her in need of a legal guardian, after the 1986 model in which they were riding rolled over.

The safety record was “frightening” with “one in 500 Bronco II’s ever produced was involved in a fatal rollover.” Automobile insurer GEICO stopped writing insurance policies for the Bronco II. By 2001, Time magazine reported that the “notorious bucking Bronco II” rollover lawsuits had “cost the company approximately $2.4 billion in damage settlements.”

So Is The Ford Bronco II That Dangerous?

There isn’t a clear answer for that. If you read enough about the Bronco II’s rollovers and the lawsuits, it definitely sounds scary. What seems bizarre is that the Bronco II has been popular with numerous off-road enthusiasts. Why haven’t they rolled over?

Maybe because off-road enthusiasts know that off-road vehicles are not sport cars, and could roll over during a quick evasive maneuver. To be a good off-roader, you have to understand center of gravity, and momentum. If you lifted the Bronco II, but kept it on the same tires, it would become even more top heavy. A sharp turn combined with the vehicles weight and momentum would cause it to tip.

But Bronco II owners don’t just lift the vehicle. They lift the vehicle to add larger tires, and gain ground clearance. Some even add stronger and wider axles. These larger tires are usually mounted on new wheels, and these new tires and wheels widen the Bronco II’s track width. The larger tires and wheels also have more weight than the stock tires and wheels. These help weight the vehicle down. So the wider track and added weight lends to the Bronco II’s stability over stock. But that doesn’t mean you can go as tall as you want. You want to keep the Bronco II as low as possible, lifted just enough to clear its larger tires.

The easiest way to demonstrate this would be to stand straight up with your feet together, and have someone push you to the side. Then spread your feet apart and have them try again. You’ll see how your wider ‘track’ gives you more stability.

Resources:

SUVs – Suddenly Upside-down Vehicles: Part I: Faulty Design

Ford Bronco II rollover lawsuits may be reheard as expert witness is challenged